Analyst Bjørn-Erik Orskaug at DnB NOR Markets presents three arguments for NOT bailing out Greece, and asks the simple question; why should the tax payers of the European Union pay for Greek irresponsibility and stupidity?

“It is difficult to argue that the debt problems are undeserved.”

Bjørn-Erik Orskaug

There are strong arguments for not bailing out Greece of their debt problems, senior economist Bjørn-Erik Orskaug writes in a research paper. It might put a damper on the short term insecurity, but the problems of sovereign debt in Europe won’t go away, Mr.Orskaug points out.

“The short-term liquidity problems for Greece makes it, in our opinion, just as likely that other countries in the euro zone will help out, as the Greek authorities will take care of the problems themself,” Mr. Orskaug writes.

“A Greek debt default is highly unlikely in the short term. In the next few months the fear of failure will probably persist, but then it should be curbed. The long-term solvency problems are not going to be resolved soon. And they apply to many more EU and eurozone countries than Greece. The only solution is fiscal tightening. A pressured national financial situation of varying degrees for different euro countries might lead to higher interest rates, and low and divergent economic growth.”

DnB NOR Markets have been arguing that it’s unlikely that the European Union will let Greece go bankrupt, and is still of that opinion.

But in the research note the analyst Bjørn-Erik Orskaug takes a closer look at the consequences of such an action.

First some history:

The fact that Greece has a large debt burden is old news.

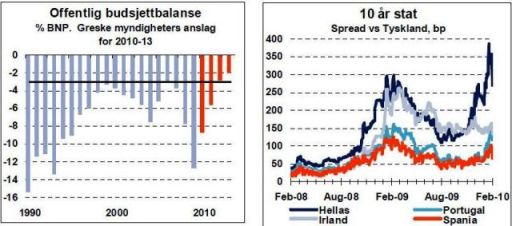

Only in one of the last 20 years the country’s budget deficit has been below 3%, and Greece have had a national debt of more than 100% of GDP since the 90’s.

In 2009 it looked like the debt situation in Greece would be better than in most Mediterranean countries with a deficit of 6,7% of GDP, but in December the Greece authorities said it would be 12,7% instead.

Suddenly the problems became acute.

Based on the fiscal policy estimated by the European Commission for the years ahead, the Greek government‘s gross debt will rise to 135 percent in 2011. If fiscal policy is not changed, and at the same time the costs associated with maturity is rising, the debt level in 2030 will be about 200 percent.

Sharpen Up Or Default

So, what can a country do if the debt is no longer sustainable? the Norwegian analyst asks.

“The obvious solution is a combination of raising taxes, cutting spending and introducing structural reforms. Otherwise, there are essentially three options. The authorities can inflate off the debt (print money), devalue its currency (reduce the burden of debt in domestic currency), or choose not to repay (default). For a country in the euro zone neither inflating or devaluation possible, because it is the European Central Bank (ECB) that is governing the amount of euros in circulation. Greece has therefor only two options: Sharpen up or defaulting.”

Fear of failure is the reason that risk premiums on the governments debt and the Greek prime rates have increased dramatically recently.

For example, the difference between interest rate on the Greek and the German government debt (10 years) has increased from around 240 bp. at the years end to 386 bp. in late January.

Concern has also increased in relation to countries such as Portugal and Spain, but for these countries the interest rate is differential and still significantly lower. The interest rate differential for the Irish government debt is the second highest in the euro zone, at 133 bp. But this has evolved almost flat after the authorities in Ireland, implemented strong fiscal cutbacks.

The yield on 10 year government bonds at 6.7 percent is extra hard to handle when the gross debt is around 110 – 120 percent of GDP, as it is now. And market participants’ doubts about the solvency can provide an explosive debt dynamics.

Higher government interest rates make it harder to service the debt and increase the need for fiscal tightening.

At the same time private loan interest rates rise as a result of higher government interest rates.

Both parts will dampen economic growth, which in turn will result in lower tax revenues, increased fears of default and the need for further tightening. A snowball is rolling.

This is the background for the plans which now will are being formed. Because of pressures from both the financial markets and the rest of Europe, it is expected that Greek authorities will cut budget deficits.

Spending cuts, increased tax collection and pension reform will reduce the deficit to 8.7 percent this year and then to 2.8 percent in 2012.

The European Commission approved last week the Greek plan, with substantial reservations (including demands for details on implementation).

The next step is that the finance ministers of the EU (ECOFIN) formally approves the plan.

“But the responses so far indicate that financial markets do not trust the Greek authorities’ ability and willingness to correct its course. Even thou there’s now plans in the EU for how Greece may be supported to get through the potential liquidity squeeze in the coming months.”

Why Should EU Save Greece?

“Why save Greece at all? There are at least three arguments as why such an action should not happen. The first argument is that a rescue mission will be a default and a subsequent restructuring of the national debt will get the economy out of the crisis in better condition than it went into it. History suggests that such a process is painful, as a country that will be banned from capital markets, the budgetary readjustments will be enormous. A better argument are in place in form potential moral hazard: If a country is salvaged, the other countries in the euro zone could expect the same. It can then be detrimental to budgetary discipline in Europe – and even the european cooperation. The third, and perhaps equally weighty argument is that it is bloody unfair for taxpayers in the country that has kept its budgetary obligations to pay for those who have not done it. The European Union is characterized by solidarity, but there has to be a limit to rewarding irresponsibility and stupidity.” Bjørn-Erik Orskaug at DnB NOR Markets writes.

Bailout, Still

“We believe, however, the three arguments FOR a rescue weighs heavier. First, the contagion effects on the rest of the euro zone by a Greek bankruptcy is large. Implicit in the pricing of the Portuguese, Spanish and Irish debt is probably already the assumption that the EU will not let these countries defaulting. Disappears this assumption, the interest rates may rise sharply.”

“Second, banks in Europe are sitting on a lot of Greek government debt. Exactly how much is uncertain, but French, Swiss and German banks are together exposed to the Greek debt to a value of around EUR 200 billion.”

“And third: a bankruptcy within the euro zone would be a declaration of failure – in support of all those who have always believed that the euro cooperation will not survive in the long run. The loss of prestige would be enormous.”

“Due to factors such as moral hazard and concern for the taxpayers in other euro countries, and the regulations, the support from the IMF might be a relevant solution. We belive, however, that the most likely solution includes support from Germany and other european countries with strong state finances. In order to please their own taxpayers, it is also likely that support will come in the form of guarantees and not direct payments. And to prevent moral hazard, a potential rescue package will involve strict requirements for Greece.”

The Problem Won’t Go Away

“The long-term solvency problems will however not disaper instantly. The problems are huge also for countries such as Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Belgium and maybe even France. They can not be solved by other countries assistance, the sums are too large and most developed countries have their own long-term debt challenges to deal with.”

“Even if we believe the short-term problems will be fixed in a way that avoids a major financial shock in the near term, the focus will continue to be on budget policy tightening in the euro zone in the coming years. The pressure upon government rates will be substatial and economic growth is likely to vary widely from country to country. Divergence is likely to be an important feature in the euro zone’s cyclical upswing, which makes the job even harder for the ECB.”

Here’s a copy of the research note from DnB NOR Markets (Only available in Norwegian).

Related by the Econotwist:

EU Wants Answers From Wall St. On Greek Debt

Attacks Against Spanish Financial Markets?

Germany Organizing Greek Bailout

Traders Short Record Amount of Euro

Global Markets: “The Fear Is Still Out There”

Denmark In Danger Of Becoming The “New Greece”

The Greek Bond Bomb Keeps Ticking

And The Euro Came Tumbling Down

Related articles by Zemanta

- Greece Needs Help, But Can the EU Bureaucracy Save It? (seekingalpha.com)

- Greece facing Goldman Sachs debt deal scrutiny (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- E.C.B. President Defends Measures on Greece (nytimes.com)

- Greece under debt pressure at eurozone talk (financialpost.com)

- Greek PM slams European Union amid crisis (cnn.com)

- European Ministers Prepared to Impose More Measures on Greece (businessweek.com)

- Greek Currency Swap Draws New Scrutiny (online.wsj.com)

- Goldman Sachs, Greece Didn’t Disclose Swap Contract (Update1) (businessweek.com)

- Greece calls EU plans ‘timid’ (news.bbc.co.uk)

- Greece facing Goldman Sachs debt deal scrutiny (sfgate.com)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)

Thanks for the great post!

Thanks for visiting 🙂

econotwist